To both students and collectors of woodblock prints, the issue of "original editions" versus "later editions" is always of interest and certainly a concern. Much of this uncertainty is lessened by the ability to read the various printer's seals found in the prints' margins, coupled with the knowledge of the time periods as to when these various printers did their work.

Certainly of related interest to this matter is the question of whether the blocks used were all originals or if some (or all) were possibly recarved. To make this determination and to thusly exclude this possibility, it is necessary to have in hand for direct comparison either a "known original" or a fairly large, well-printed facsimile as a reference for comparison. Later we will discuss this more.

Japanese woodblock artisans, both carvers and printers, are superb craftsmen beyond refute and their works are certainly worthy of our admiration. Understandably then, with the demand for and subsequent high prices realized from the sale of certain well-known prints, it is no wonder then that many popular early ukiyo-e prints (Hiroshige's and Utamaro's are commonly seen) have been recarved and issued as re-strikes. Generally, most of these later versions are knowingly produced and honestly represented when sold as being "reproductions" produced from "recarved blocks". However occasionally, whether through outright fraud or by honest ignorance, such later copies are at times presented and offered as originals. To protect oneself then, the buyer must possess either the accumulated knowledge and ability to make this determination for himself, or hold complete confidence and trust in his seller.

| Return to top |

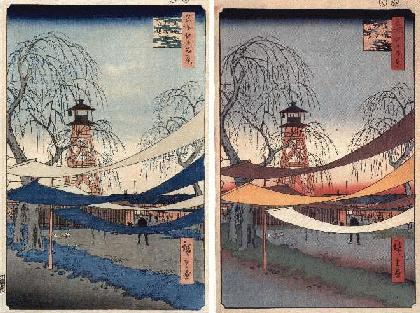

As a quick example of the usefulness of this side-by-side comparison method, shown below is a "subject" Hiroshige print, titled "Hatsune Riding Grounds, Bakuro-cho" and printed in 1857. The print on the left was recently obtained by this author in an online auction. We compare it directly against the image on the right, a "known first edition original" at the Brooklyn Museum, illustrated as Plate 6 in Henry Smith's superb reference One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

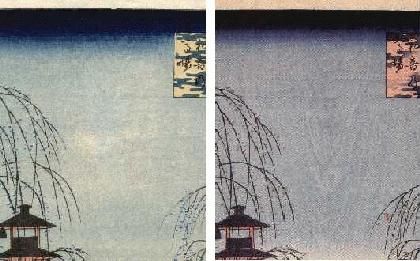

Admittedly the colors used are different (printers and publishers often experimented with color variations), but the visible woodgrain pattern seen in the central sky of both prints (see below), like a human fingerprint, is irrefutable. This is a simple comparison anyone could make; originality and authenticity thusly supported.

| Return to top |

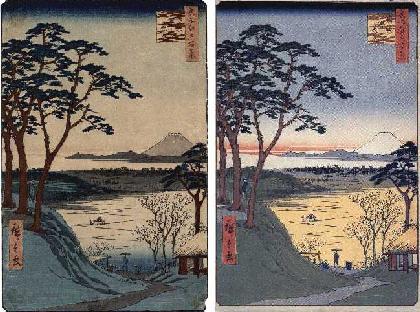

A second quick example of the usefulness of this side-by-side comparison method, is another "subject" Hiroshige print (below left) recently obtained by this author in an online auction compared directly against yet another "known first edition original" (below right). This 1857 print is titled "Grandpa's Teahouse at Meguro"; the image below right is also from the Brooklyn Museum, Plate 84 in the same reference noted above.

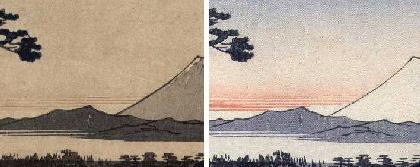

In this case, the original greens of the auction-purchased print have over time faded into what now appears as blue, which often happens due to damaging effects of prolonged light exposure. Nevertheless, a close examination of both prints reveals the exact same woodblock "flaw" (a double-nick or dent) seen in the middle of the distant gray hill of each print (see below). Again, much like a human fingerprint, the proof that both were printed from the same woodblocks is indicated.

| Return to top |

Fortunately, in the case of later prints known as shin hanga the occurrence of recarved blocks is much less of a concern. This is likely the result of two factors. First, most shin hanga prints are currently much less valuable than rare, early ukiyo-e, and second, recent years have seen a marked decline in the number of new Japanese artisans with both the ability and willingness to undertake this trade.

![]() However, re-strikes of certain shin hanga prints do exist. A notable example is a popular series of bijin-ga prints by Torii Kotondo, published by Ishukankokai.

However, re-strikes of certain shin hanga prints do exist. A notable example is a popular series of bijin-ga prints by Torii Kotondo, published by Ishukankokai. ![]()

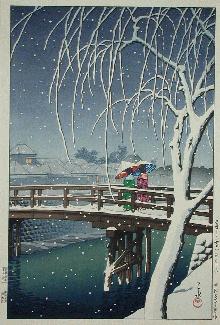

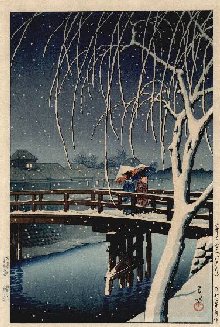

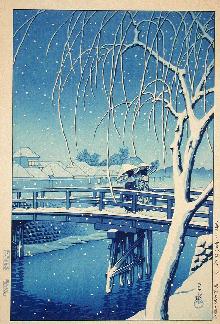

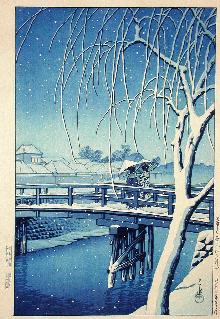

Here we examine "Edogawa no Yuki", a popular Hasui print published by Doi Hangaten. It makes a good recarving case study, since there appear to be many editions and alterations -- we will try to bring some "order to the chaos". The following chronology is our personal opinion only, and we welcome any input and images of the missing prints or other versions.

| Return to top |

This format allows you to click and enlarge the images, to compare the woodblocks' carved details side by side.

|

Publisher Seal: Doi Teiichi

Estimated publishing period: 1932 - ?? | |

|

|

|

| Return to top |

|

Publisher Seal: Doi Hangaten

Estimated publishing period: unknown | |||

|

|

| ||

| Return to top |

|

Publisher Seal: Doi Hangaten

Estimated publishing period: ?? - 1965 | |

|

|

|

| Return to top |

|

Publisher Seal: Doi Eiichi

Estimated publishing period: 1965 - 1993 | |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Return to top |

|

Publisher Seal: Doi Eiichi

Estimated publishing period: 1993 - ?? | ||

|

|

| |

|

This version seems to be an incomplete copy - some blocks are missing. | ||

| Return to top |

And, for those who just can't get enough, here is a final teaser -- the Edogawa postcards!

|

Publisher Seal: Doi

Estimated publishing period: ?? |

[ medium ] [ huge ] |

If these blocks are not the same, the question might be -- why recarve a postcard? A possible answer is that multiple images were carved into a single keyblock. Your feedback is welcomed -- please send in your comments, suggestions and print images.

| Return to top |

Here's another shin hanga print with some apparently recarved blocks, this one published by Watanabe. "Evening Rain at Ueno Yanaka Pagoda" is a popular Shiro Kasamatsu print, first published prewar. The two versions shown here (without date block in the margin) are postwar, bearing the 6 mm Watanabe seal.

Compare the umbrella - the ochre stripe around the umbrella, and the woman's hands. Other differences also seem to be present, on close examination.

|

|

We note that this print is commonly available today as a Heisei version with a 7 mm seal. This version has the wide ochre band around the umbrella and the fingers of the geisha are "amputated". So it seems that the narrow band indicates the early version, the wide band the recut blocks. The change probably happened somewhere between 1946 and the late 1950's.

| Return to top |

Your feedback is welcomed -- please send in your comments, suggestions and print images.

Original text as written and submitted by Andreas Grund for this article is his property, copyright © 2000, all rights reserved. Original text as written and submitted by Thomas Crossland for this article is his property, copyright © 2000, all rights reserved.

| Return to top |

|

|

|