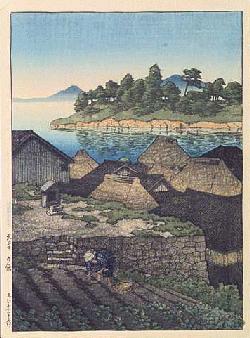

The venerable auction house Butterfield & Butterfield recently offered this well-researched Hasui print as an eBay "Premier" auction. ![]()

We were impressed that Butterfields was still able to perform such top-drawer shin hanga cataloguing, so soon after massive layoffs imposed by its parent company eBay, and directly after eBay pulled the plug on its "Great Collections" venue ![]() .

.

Butterfields carefully described this item as a posthumous reprint. Realizing this must be a previously undocumented Hasui commemorative or private edition, we're drawn to this auction like a moth to flame. But we're careful too; this case study describes our efforts to prove that this print is indeed a (rare, unrecorded) reprint, as described.

Before the Auction Closing

We begin by examining the written description of the print, in the Butterfields "Premier" auction listing:

Condition: color and impression good. Paper slightly toned, small margin tears in upper left corner and lower left side, slight wrinkling, three pieces of tape on the reverse. Narrow 3/8" (.5cm) margin is possibly trimmed.

Low Estimate: $300

High Estimate: $500

The estimates are the total for 3 woodblock prints, the other two being early Koson kacho-e prints. The low figures are encouraging; apparently Butterfields doesn't consider this Hasui reprint to be highly valuable (despite its being undocumented and surely quite rare).

We note only that the exact title is not given, and that the size stated does not indicate whether this is the image size or paper size.

| Return to top |

The familiar round Watanabe seal can be glimpsed in the lower right corner, its exact size not stated.

A title and date can be seen in the lower left margin, and one can barely see that the date might indeed read Taisho 11, or 1922. ![]()

| Return to top |

Before hitting the books, we consider that Watanabe's wood blocks were supposedly all destroyed in Tokyo's Great Fire and Earthquake of September 1, 1923. So if this print is indeed a posthumous reprint as we intend to prove, either some blocks actually did survive or the blocks were recarved. Any differences might be subtle, but we're determined to find them.

Knowing that an "experienced" shin hanga collector is one who exists in a foggy landscape of ever-bending rules and shattered truths once held dear, we proceed with an open mind.

| Return to top |

Collectors have many reference books available, though they vary in completeness, accuracy, and availability. We turn first to the most common reference, Merritt &Yamada, quickly confirming on page 235 that Watanabe did publish a Hasui print "Amakusa Goryô" in 1922. It's listed in the 36-print travel series "Selection of Scenes of Japan (Nihon Fûkei senshû), 1922-1926", and its size is listed as 28 x 21 cm.

Here we find encouraging news. This size does not agree with the 12 x 8" (26.4 x 17.5 cm) size given in the auction listing, our first confirmation that this print may not be original. We already noted that the listing did not state whether the dimensions were the traditional image size, or the hard-to-use paper size. But since the listing dimensions are smaller than the Merritt & Yamada image size, we suspect this could indeed be a recarved print.

Could the problem be explained through an incorrect or clumsy conversion between centimeters and inches (a common error in the woodblock field)? Specifically, we don't know whether the Butterfield print was directly measured using inches or centimeters. If we trust the 12 x 8", this would yield 30.5 x 20.3 cm. This is taller and slight narrower than the Merritt & Yamada size of 28 x 21 cm, and does not remotely agree with the stated 26.4 x 17.5 cm. Converting the other way, the seemingly accurate 26.4 x 17.5 cm equals 10.4 x 6.9", not even close to the stated 12" x 8". Again, no help there.

| Return to top |

Next we consult a pair of quick-reference guides. The Shôgun listing gives the title as "Amakusa Goryô (Goryô in Amakusa District)". The Tierney listing reads "1922 Goryo, Amakusa (6)", indicating that Tierney observed a 6 mm seal on this print in Narazaki.

Our next library stop is Yamanashi ![]() , a very useful reference depicting 200 Hasui prints including nearly complete sets of the early travel series. This 36-print "Nihon" series is represented in plates 67 through 87, although our Amakusa print is not depicted.

, a very useful reference depicting 200 Hasui prints including nearly complete sets of the early travel series. This 36-print "Nihon" series is represented in plates 67 through 87, although our Amakusa print is not depicted.

At this point we notice that most of these 21 Yamanashi prints carry the series stamp, many in a light blue color. In general, collectors don't "require" seeing a travel series stamp, since they're not always present on exported prints. Still, we go back to the auction listing and look closely. To our surprise we realize there is a light blue "something" directly above the title, the correct place for a series stamp. How did we miss it before? (Not looking for it!)

At this point we notice that most of these 21 Yamanashi prints carry the series stamp, many in a light blue color. In general, collectors don't "require" seeing a travel series stamp, since they're not always present on exported prints. Still, we go back to the auction listing and look closely. To our surprise we realize there is a light blue "something" directly above the title, the correct place for a series stamp. How did we miss it before? (Not looking for it!)

Yamanashi yields no other information, other than to show that this series uses the unusual Hasui "stripes" seal and the round Watanabe seal. The auction image doesn't give a clear look at the Hasui seal, probably hidden in the dark foreground. A "teardrop" Hasui seal, the common one, would be a sure sign of a reprint.

Seeking the ultimate resource, we trot down to the public library and check out the neighborhood copy of Narazaki. Here we see plate number 93, showing the markings we expect: light blue series stamp and Watanabe round seal. The Hasui "stripes" seal is visible in the lower right corner, but its details are obscured. Overall the auction image seems to agree with the Narazaki image, and the Watanabe seal is located (coincidentally, we say) in exactly the same place. So far, this seems to be a very skillful recarving and/or reprinting job.

| Return to top |

After the Auction Closing

Next, we get the print.

Across the bottom (verso) is written in pencil:

Hasui. Before the earthquake. View of Amakusa.

Written by a previous collector, or a dealer? Purposely misleading, or an honest mistake? Shin hanga collectors run into this all the time.

Fortunately Butterfields had the expertise and courage to specifically refute this -- they saw the notation, did the research, and ultimately declared it to be a "posthumous reprint". In our view, the appearance of this "before the earthquake" inscription actually supports the idea that Butterfields' assertion must have been substantiated.

| Return to top |

We now turn to the simple question of measurements to confirm our recarved blocks. Recall our being puzzled at the auction listing size, 12" x 8" (26.4 x 17.5 cm).

Here are the actual measurements, taken to the outer edge of the keyblock border and the edge of the paper, respectively.

image height: 28.4 cm (11.2")

paper height: 30.5 cm (12.0")

image width: 20.6 cm (8.1")

paper width: 22.5 cm (8.9")

The image size (with rounding) agrees with the Merritt & Yamada size of 28 x 21 cm. So it seems as if the recarved-as-smaller-blocks theory, will not fly today.

Now we can better understand the Butterfields 12" x 8" description: the stated inches height was the paper size, while the stated inches width was image size. An interesting approach, not often seen. About the stated metric dimensions 26.4 x 17.5 cm, which utterly defy our attempts to explain, we must defer to the higher mastery at work here.

| Return to top |

On the actual print we can now see the red Hasui seal, obscured in the lower right corner. Instead of the Showa-era "teardrop" seal, we confirm that it's the same "stripes" seal from the prints depicted in Yamanashi and Narazaki.

On the actual print we can now see the red Hasui seal, obscured in the lower right corner. Instead of the Showa-era "teardrop" seal, we confirm that it's the same "stripes" seal from the prints depicted in Yamanashi and Narazaki.

We closely compare the geometry of the scanned red seal with the black-and-white image in Yamanashi's index. Although the reference image is less complete than our scan, there seem to be no actual discrepancies. So we have now lost another good opportunity to demonstrate that this seal (and blocks) were truly recarved.

We closely compare the geometry of the scanned red seal with the black-and-white image in Yamanashi's index. Although the reference image is less complete than our scan, there seem to be no actual discrepancies. So we have now lost another good opportunity to demonstrate that this seal (and blocks) were truly recarved.

| Return to top |

Taking a break from seals, we review the overall image. Do the keyblock details vary from the published image (in Narazaki)? Are there border 'chips' missing? Are the colors different than the book? Do the tones seem poorly balanced, unmoderated, "too bright"?

As to the printing -- are the baren marks indistinct, and do they show inappropriate placement, direction, spacing or intensity? Is the paper uniform, heavy, unchained, new? The described tape marks verso, are they fresh?

Any of these characteristics would help suggest a later production -- but unfortunately none do. The image matches in every detail; the colors also match and are well balanced. The printing and paper speak of craftsmanship, not modern production.

| Return to top |

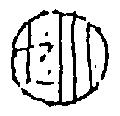

We move on to the 6 mm. If this matches one of the many catalogued postwar 6 mm or 7 mm seals, we'll have our confirmation.

We move on to the 6 mm. If this matches one of the many catalogued postwar 6 mm or 7 mm seals, we'll have our confirmation. ![]() Unfortunately, no such luck. The seal measures 6.1 mm from outer edge to outer edge, nowhere near the 7.4 mm for a seal traditionally considered "posthumous". Worse, it also doesn't match other known postwar 6 mm seals.

Unfortunately, no such luck. The seal measures 6.1 mm from outer edge to outer edge, nowhere near the 7.4 mm for a seal traditionally considered "posthumous". Worse, it also doesn't match other known postwar 6 mm seals.

The character in the lower right quadrant can be used for handy seal identification, since it varies the most among 6 mm seals. In this case it quickly ruled out a match with the many known postwar 6 mm seals. This doesn't mean it couldn't be an undiscovered late seal, but we are still lacking our definite "reprint" confirmation.

| Return to top |

![]()

Still on the front of the print, we look now at the travel series seal (shown at left). As we did with the Hasui seal, we compare our detailed scan with the Yamanashi index image (shown at right).

Still on the front of the print, we look now at the travel series seal (shown at left). As we did with the Hasui seal, we compare our detailed scan with the Yamanashi index image (shown at right).

Aha! We see some differences, these are definitely not the same seals. At last we seem to have our evidence of a recarved seal.

To check this out further, we select the most distinctive difference, one easy to spot in small book images. The scanned seal has a clear space between the 5th and 6th characters; the Yamanashi seal has none.

We then review all of the "Nihon" travel series seals which appear in Yamanashi and Narazaki. To our surprise, some seals have a space (matching our scan), and others have no space! In fact, more prints have the space than not.

Now reeling, we go back to review the Yamanashi index. ![]() We notice for the first time that there are two date ranges given for this seal, while all the other travel series seals only have one date range. The full caption can easily be read as follows:

We notice for the first time that there are two date ranges given for this seal, while all the other travel series seals only have one date range. The full caption can easily be read as follows:

|

Taisho 11 to Taisho 12 = 30 prints

Taisho 12 to Taisho 15 = 6 prints 36 prints |

Taken by itself, this caption would normally be considered, shall we say, inscrutable. But having stumbled across the two different seals, we now see the well-meaning attempt to describe two versions of the same seal, with their respective usage dates of 1922-1923 and 1923-1926. ![]() So, we're back where we started, with our scanned seal being no different than the correct early "Nihon" series seal. The re-carving craftsman must have been carefully instructed to copy the non-surviving seal design, not the surviving one.

So, we're back where we started, with our scanned seal being no different than the correct early "Nihon" series seal. The re-carving craftsman must have been carefully instructed to copy the non-surviving seal design, not the surviving one.

| Return to top |

Finally we turn the print over again. Being lazy, we've left the hardest thing for last -- an unfamiliar Japanese stamp on the verso. The number "9" seems to have been inked in by hand, along with a series of short strokes below it. This has the suggestion of a limited edition notation, which could at last be our "posthumous reprint" confirmation. Namely, if there was a commemorative reprint series, perhaps an intentionally faithful reproduction, it might make sense that the prints bear a special stamp with edition numbers. Even some original Hasui prints from 1955 carry edition numbering

Finally we turn the print over again. Being lazy, we've left the hardest thing for last -- an unfamiliar Japanese stamp on the verso. The number "9" seems to have been inked in by hand, along with a series of short strokes below it. This has the suggestion of a limited edition notation, which could at last be our "posthumous reprint" confirmation. Namely, if there was a commemorative reprint series, perhaps an intentionally faithful reproduction, it might make sense that the prints bear a special stamp with edition numbers. Even some original Hasui prints from 1955 carry edition numbering ![]() , and other postwar shin hanga examples may exist.

, and other postwar shin hanga examples may exist.

Turning over this last stone required asking for assistance from the worldwide shin hanga community. A global distress call, kind of a virtual BatSignal ![]() , brought this prompt reply from overseas:

, brought this prompt reply from overseas:

Right column from top to down:

- first three kanji (sanbyakumai) means "three hundred prints"

- following kanji and hiragana (kagiri) means "only"

- last two kanji (zeppan) means "no further edition"

Left column:

- first kanji (dai) & last kanji (ban) means "edition number"

- added dark red characters mean individual number for a print

- first number reads nine but following numbers unread (right side missing?)

I hope this information clears your obscurity.

![]()

With a thousand thanks, our obscurity is now much more clear.

| Return to top |

Regarding the short strokes following the character "9", we found a possible explanation on our own. These strokes appear to be simply space-fillers, to prevent other numbers from being entered. We see the same strokes filling the space between title and date in other Hasui travel series prints. So it's reasonable to consider that the same technique would be used here -- all the more remarkable if they used it 50 years later!

Getting back to the edition numbering -- some days later this helpful addendum arrives:

According to his notice, "These series should start from June in 1922 with 3 prints each on a monthly basis under a limited edition of 300 sheets. I would take full responsibility for selecting only perfect-condition prints by putting edition numbers. Once their respective printing was over, I would break their wood block and never reprint them by any means."

In fact he published plate #82 through plate #111 by mid-1923 and then he suffered from The Great Earthquake during which he was in the process of printing plate #112. In such circumstances I believe all the prints from #82 through #111 could be pre-earthquake ones bearing edition markings of 300 respectively. I recall I surely saw such edition markings on the back of

prints #87 & #97 at a domestic gallery [in Japan].![]()

At this point we don't feel the least embarrassed that we didn't know this already. After all, who among us can browse through Narazaki like it's a dime novel?

| Return to top |

Except that weeks later, in a routine reference lookup, we came across these paragraphs in Pachter:

In 1923, as the series was being completed, the great Kanto earthquake and fire struck. The blocks were indeed destroyed, as were all unsold prints, Watanabe's business establishment, Hasui's home, sketches and notes, and much of Tokyo and the surrounding area. Thereafter, Watanabe did not promise that blocks would be destroyed, nor did he number Hasui's later prints. ![]()

So, in fact we should have known sooner. Further, upon going back to the Shôgun listing, we notice many early titles (including our "Amakusa") have an asterisk, with the footnote reading "Limited to an edition of 300 impressions".

This seal, our last chance for proving the reprint, has turned out to be hopelessly consistent with the well-documented, genuine pre-earthquake seal.

| Return to top |

Conclusion

Sadly, thus far no direct or circumstantial confirmation of the Butterfields "posthumous reprint" description can be established. In our efforts to do so, we have nearly suggested the opposite -- hardly the result we set out to achieve.

We fear now that this print is not at all as advertised, and not the unrecorded special edition we had hoped for. Instead it could just be an old pre-earthquake Hasui, number 9 of 300, with nice colors. That famous Roman general, Caveat Emptor, has once again taught us his unwelcome lesson.

And so we soldier on, as shin hanga collectors must do, hoping that tomorrow might bring the undiscovered treasures we dream of.

| Return to top |

|